In our Vietnam War unit, I wanted students to go beyond just memorizing a political timeline. I wanted them to understand how geography, including location, movement, regions, and human-environment interaction, shaped the war in lasting ways. To explore that, we tried something different: a museum exhibit project built around the Five Themes of Geography.

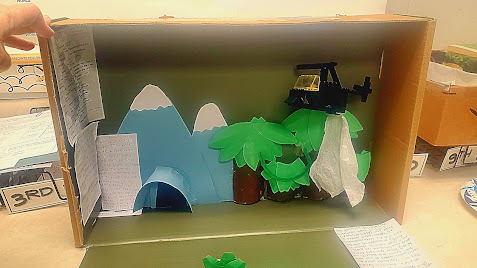

Students worked on their own or with a partner to research and design exhibits that connected the war to at least three of the five geography themes: Location, Place, Human-Environment Interaction, Movement, and Region. Each project needed to include one artifact or display for each theme used, along with a short written explanation. Some created slide decks, others used poster boards or dioramas. One student built a LEGO helicopter hovering over a jungle scene with small soldiers below. It was his way of showing how Vietnam’s dense landscape shaped U.S. military strategy.

What stood out most was not the creativity. It was the thought behind it.

One group mapped the Ho Chi Minh Trail and started asking how supply routes worked when the U.S. controlled the skies. Another pair compared North and South Vietnam, adding maps, flags, leader quotes, and photos. Their write-up started with basic facts about political divisions, but by the end they were asking whether the war was inevitable after the country was split.

That led to some powerful questions:

“Did the U.S. understand the geography at all?”

“Is Agent Orange still affecting the land?”

The geography themes gave students structure, but they also left room for deeper thinking. I noticed how often students came back to the human side, including stories of civilians, soldiers, refugees, tunnels, and the physical challenges of the landscape itself.

One student, after reading about the Cu Chi tunnels, asked to build a cutaway model for the Human-Environment Interaction theme. He wanted to focus on how people adapted, not just how they suffered. Another student brought in a story her grandfather had finally shared. He served in Vietnam but rarely spoke about it. Her group included a short piece of his memory next to their display on Movement.

This kind of project brought more discussion, more movement around the room, and more mess, but it was the kind of mess that comes with real thinking. I saw students checking timelines and trying to label terrain features clearly for an audience who might not know much about the war.

All the required standards were still there. They used maps, analyzed primary sources, and explained cause and effect. What I valued most was how this project helped them think about place and space. They were not just recalling what happened. They were working out why it happened where it did.

We wrapped up with a gallery walk so students could view each other's exhibits. I asked them to leave sticky notes with questions or connections. Some wrote things like, “I didn’t know there was so much jungle,” or “This reminds me of the war in Ukraine now.”

If you are planning a Vietnam War unit and want to bring in geography in a way that feels connected and thoughtful, not just memorizing maps, this kind of project might be worth trying. It brings together research, analysis, creativity, and conversation. The questions students ask along the way tend to stay with them long after the unit ends.

If you’d like a copy of this lesson, you can find it here.

You can find my Vietnam War Bundle here.

.jpg)

Comments